The identification, recognition and use of local and indigenous knowledge in Integrated Water Resources Management responds to water governance processes.

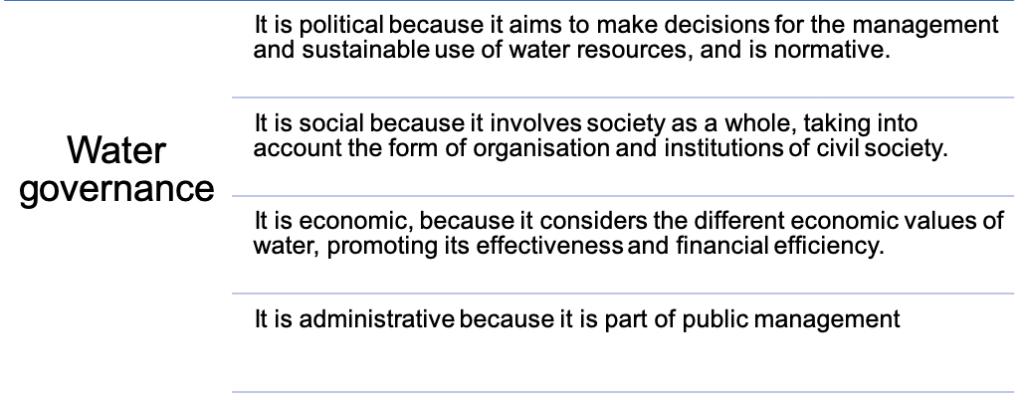

Water governance is a political, social, economic and administrative system that aims to manage water resources and the provision of water services at different levels of society through participatory procedures (Rogers and Hall 2003, Batchelor 2003, Campos and Carlier 2019).

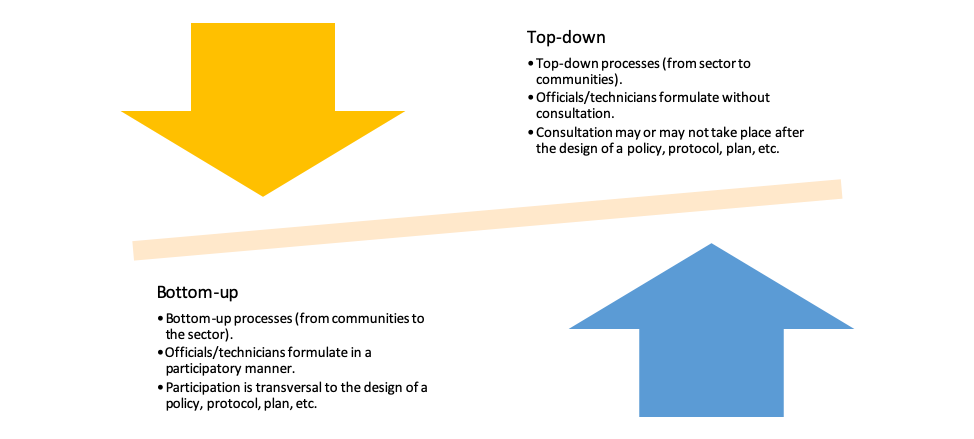

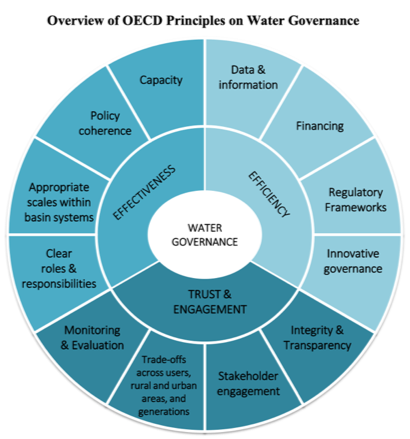

According to the OECD’s principles of water governance (2015), water governance should be built through an approach where “Top-Down” and “Bottom-up” perspectives are in dialogue. In this regard, they state that “governance is successful if it helps to solve key water challenges using a combination of bottom-up and top-down processes, while fostering constructive relationships between the state and society.” (OECD 2015, 5) [1].

Bottom-up processes, also referred to as bottom-up, consist of identifying, formulating and implementing actions based on dialogue with community-based organisations, i.e. institutions that represent the citizens of the communities. In this sense, they are multi-actor and inclusive processes. In contrast, the “Top-Down” or Top-Down approach to water management focuses on the generation, implementation and monitoring of norms, action plans, among others, from the governmental level.

The dialogue between bottom-up and top-down approaches allows water governance for IWRM to be built in a participatory way, incorporating local and indigenous knowledge and perspectives, where appropriate, into technical knowledge.

Fostering water governance requires a range of skills and knowledge. It is often considered that the technical soundness with which they can build water infrastructure or an IWRM plan is sufficient. Increasingly, however, there is a type of skill that is seen as fundamental to fostering good water governance: soft skills.

According to the OECD, soft skills have become more prominent in the water resources agenda because one of the dimensions of water governance: trust and participation, with four of its principles being, 1) monitoring and evaluation, 2) Trade-offs across users, rural and urban areas, and generations, 3) stakeholder engagement, and 4) integrity and transparency.

2.1. Soft skills

Soft skills – also called soft skills or transferable skills – are those that allow us to adapt to different contexts and perform in different social and work environments (UNESCO 2018, UNICEF 2019).

Transferable skills, also known as life skills, 21st century skills, soft skills, or socio-emotional skills allow young people to become agile, adaptive learners and citizens equipped to navigate personal, academic, social, and economic challenges; transferable skills include problem solving, negotiation, managing emotions, empathy, and communication and support crisis-affected young people to cope with trauma and build resilience in the face of adversity; transferable skills work alongside knowledge and values to connect, reinforce, and develop other skills and build further knowledge.

Source: UNICEF (2019). Global Framework on Transferable Skills [2]

In the framework of water and climate change governance, soft skills fulfil three key roles:

- Enhance capacities for communication, dialogue and relations with local actors: officials/technicians in water sector institutions foster dialogue and build trusting and sustainable relationships with communities and other actors at local levels, ensuring respect and appreciation of cultural diversity and gender sensitivity.

- Build capacities for negotiation, conflict prevention and resolution: officials/technicians in water sector institutions have the skills to foster social climates of dialogue, cooperation and peace, managing disputes and generating agreements in a participatory manner.

- Strengthen community involvement: officials/technicians in water sector institutions engage communities for sustained participation in IWRM, ensuring that women have an equal voice in decision-making and information production.

2.2. Engagement and trust

Engagement and trust is one of the three dimensions of water governance. It is underpinned by four principles (see accordions below). Enabling its implementation requires both hard skills and soft skills.

Engagement is a process through which different parties or stakeholders actively engage with a specific activity or issue. In the framework of water governance, participation needs to be institutionalised, i.e. it is constantly practised and has instruments (e.g. manuals) that indicate the way to engage in it.

Through engagement in water governance, local communities – as one of the stakeholders involved in IWRM – have the opportunity to contribute with their knowledge, be informed about water sector proposals, access information on project progress and make suggestions. All these actions, taken together, help to build trust.

Principles of the engagement and trust dimension of water governance according to the OECD.

Monitoring and evaluation (click to expand)

a) Promoting dedicated institutions for monitoring and evaluation that are endowed with sufficient capacity, appropriate degree of independence and resources, as well as the necessary instruments; b) Developing reliable monitoring and reporting mechanisms to effectively guide decision-making; c) Assessing to what extent water policy fulfils the intended outcomes and water governance frameworks are fit for purpose; and d) Encouraging timely and transparent sharing of the evaluation results and adapting strategies as new information become available.Trade-offs across users, rural and urban areas, and generations (click to expand)

a) Promoting non-discriminatory participation in decision-making across people, especially vulnerable groups and people living in remote areas; b) Empowering local authorities and users to identify and address barriers to access quality water services and resources and promoting rural-urban co-operation including through greater partnership between water institutions and spatial planners; c) Promoting public debate on the risks and costs associated with too much, too little or too polluted water to raise awareness, build consensus on who pays for what, and contribute to better affordability and sustainability now and in the future; and d) Encouraging evidence-based assessment of the distributional consequences of water-related policies on citizens, water users and places to guide decision-making.Stakeholder engagement (click to expand)

a) Mapping public, private and non-profit actors who have a stake in the outcome or who are likely to be affected by water-related decisions, as well as their responsibilities, core motivations and interactions; b) Paying special attention to under-represented categories (youth, the poor, women, indigenous people, domestic users) newcomers (property developers, institutional investors) and other water- related stakeholders and institutions; c) Defining the line of decision-making and the expected use of stakeholders’ inputs, and mitigating power imbalances and risks of consultation capture from over-represented or overly vocal categories, as well as between expert and non-expert voices; d) Encouraging capacity development of relevant stakeholders as well as accurate, timely and reliable information, as appropriate; e) Assessing the process and outcomes of stakeholder engagement to learn, adjust and improve accordingly, including the evaluation of costs and benefits of engagement processes; f) Promoting legal and institutional frameworks, organisational structures and responsible authorities that are conducive to stakeholder engagement, taking account of local circumstances, needs and capacities; and g) Customising the type and level of stakeholder engagement to the needs and keeping the process flexible to adapt to changing circumstances.Integrity and transparency (click to expand)

a) Promoting legal and institutional frameworks that hold decision-makers and stakeholders accountable, such as the right to information and independent authorities to investigate water related issues and law enforcement ; b) Encouraging norms, codes of conduct or charters on integrity and transparency in national or local contexts and monitoring their implementation; c) Establishing clear accountability and control mechanisms for transparent water policy making and implementation ; d) Diagnosing and mapping on a regular basis existing or potential drivers of corruption and risks in all water-related institutions at different levels, including for public procurement; and e) Adopting multi-stakeholder approaches, dedicated tools and action plans to identify and address water integrity and transparency gaps (e.g. integrity scans/pacts, risk analysis, social witnesses).Source: OECD (2015). OECD Principles of Water Governance.

In the case of territories with an indigenous population, the water sector must assess whether community participation should be contextualised within ILO Convention 169. For this, it is necessary to identify whether the country has ratified it and/or developed any regulations to implement it in the national territory, since ILO Convention 169 establishes that indigenous peoples have the right to be consulted when development measures are to be implemented within their territories.

A fundamental element in building engagement and trust is communication. Conveying information and ensuring that it is understood, valued, and used by the entire population is not always an easy task. For this reason, it should not only be based on the elaboration of communication products such as infographics, videos, posters, etc. It is necessary to promote dialogue, which is defined as a process of exchanging knowledge and points of view in order to reach agreements between different parties.

Dialogue is explored as a central mechanism within the social integration process. In turn, social integration is seen as central within the broad endeavours of peace, development and human rights, as outlined by consensus at the World Summit for Social Development, held in Copenhagen from 6 to 12 March 1995.

Source: United Nations (2007). Participatory Dialogue: Towards a Stable, Safe and Just Society for All[3]

It is important to bear in mind that when dialogue involves rural communities and indigenous peoples, it must be appropriate to the culture, local forms of communication and codes of the communities [4].

References

[1] Available in spanish: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/regionaldevelopment/OECD-Principles-Water-spanish.pdf and in english: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/regionaldevelopment/OECD-Principles-on-Water-Governance-en.pdf

[2] Available in English at: https://www.unicef.org/media/64751/file/Global-framework-on-transferable-skills-2019.pdf

Available in Spanish at: https://www.unicef.org/lac/sites/unicef.org.lac/files/2020-07/Importancia-Desarrollo-Habilidades-Transferibles-ALC_0.pdf

[3] Available at: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/publications/prtcptry_dlg(full_version).pdf.

[4] https://en.unesco.org/themes/intercultural-dialogue