4.1. Climate-resilient Planning

Data collection

To incorporate climate vulnerability assessments into their business planning framework, water utilities must understand possible risks and consequences, and how much they will cost. Assessing the impacts of and vulnerability to climate change and subsequently working out adaptation options requires good quality information. This information includes climate data, such as temperature, rainfall, sea surface temperature, sea level rise, wind speeds, tropical cyclones (including hurricanes and typhoons), and non-climatic data, such as the current situation on the ground for different sectors including water resources, agriculture and food security, human health, terrestrial ecosystems and biodiversity, and coastal zones. The greatest risk to freshwater resources may be reduced availability due to drying trends. Large uncertainty remains in terms of projected rainfall intensity, duration, and frequency.

For countries to understand their local climate better and thus be able to predict local climate change, they must have adequate national observational networks, and access to the data available from other global and regional networks. For example, monitoring trends of sea surface temperature and sea level are essential in order to assess their impacts on the increased intensity of tropical cyclones and storm surge. Within the Caribbean, CIMH prepares various thematic climatic bulletins (drought bulletins, tourism climatic bulletins, agro-meteorological bulletins, etc.), supporting informed decision-making.

In addition, local communities, women and men, must be involved in data collection and observation, as resilience is a joint process rather than top-down. For example, in Trinidad and Tobago, communities are taught to do their own water quality measurements, and young people are taught to be Water Warriors where they police the river, as part of the Adopt A River programme. As a result of this programme, the community monitors the rivers and watershed for the utility.

Note: Involving communities in data collection both strengthens resilience and enables efficient use of utility resources.

Exercise (10 min)

- Identify the types of data needed to assess the vulnerability of a community to climate change.

- Are these data being collected and if so by which agency?

- Who should be the repository of such data?

- Identify training needs for proper data collection.

IWRM and Climate Resilience

Climate change impacts do not happen in isolation; impacts in one sector can adversely or positively affect another. Thus, water resources management must follow an integrated approach. When addressing climate risks, it is therefore important to address the impacts on the major water resources (either surface or groundwater or both) and water uses (e.g. drinking water supply and sanitation, agriculture, tourism).

The most effective adaptation approaches for developing countries are those addressing a range of environmental stresses and factors. Strategies and programmes are more likely to succeed if they link with efforts aimed at poverty alleviation, enhancing food security and water availability, combating land degradation and reducing loss of biological diversity and ecosystem services, as well as improving adaptive capacity.

A regional approach is key to addressing the diversity of climate risk management options and opportunities in the Caribbean countries. To this end, the CCCCC has been supported by HR Wallingford in undertaking a climate vulnerability assessment of the CARIFORUM countries. Climate risk management should also be addressed at the highest level, by National Climate Change (UNFCCC) Focal Points in conjunction with the Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency (CDEMA) and the Permanent Secretaries’ Cabinets.

Note: Available tools: The 2017 USAID Toolkit for Climate-resilient Water Utility Operations includes a Vulnerability Assessment spreadsheet that enables utilities to quantify climate risks. HR Wallingford (2019) has developed the WaterRiSK approach to identify strengths and weaknesses and opportunity and priorities to enhance climate resilience of water supply services.

Video: The Significance of Water Security (5:44 min)

Watch the video of the Caribbean Community Climate Change Center on Building resilience and water security.

Case Study: Assessing Climate Change Impacts on Coral Reef Ecosystems and Societal Implications

Over 50% of the 44 million inhabitants of the Caribbean live within 1.5 km of the coast. In some cities, the population resides in low-elevation coastal zones (LECZs) located less than 10 m above the sea level. Coastal ecosystems such as coral reefs, mangroves and sea grass beds provide crucial shoreline protection for sea-level rise and storm surges. In addition, many of the people in the coastal zone are dependent on the sea for their livelihoods, for example through fisheries and tourism.

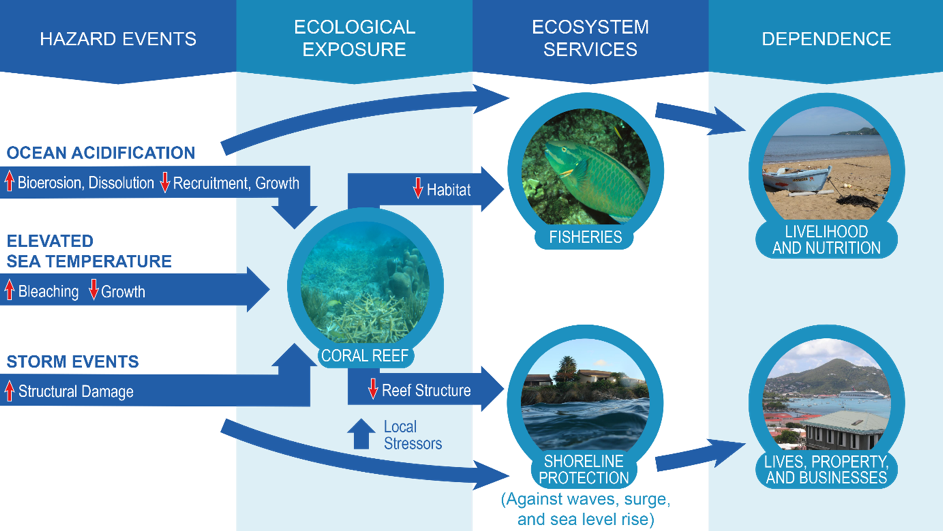

The figure below shows the connections between climate-related impacts (ocean acidification and warming as well as severe storms), responses of marine habitats and species to these impacts, and, ultimately, the effects to ecosystem services (such as fisheries and shoreline protection) and, in turn, the human community.

Specifically, the figure depicts how degradation of coral reefs due to climate change is expected to affect fisheries and the economies that depend on them as habitat is lost. The figure also shows how reef degradation decreases shoreline protection for local communities, which affects the economy and human populations more generally.

The CCORAL Tool

The CCORAL Tool (by the CCCCC) is a knowledge management system which helps decision makers to see all kinds of activities through a ‘climate’ or ‘climate change’ lens, and to identify actions that minimize the climate risks.

https://www.caribbeanclimate.bz/caribbean-climate-chage-tools/tools/

CCORAL is designed to add risk management in decision making. It takes a pragmatic approach, promoting the right tools and techniques to fit the Caribbean context, taking into account available time and resources and uncertainty about climate variability and change. Users are encouraged to prioritize their efforts and use those components of CCORAL that are of most value to them.

CCORAL contains a resources database of nearly 80 tools. These were selected from the over 100 tools initially evaluated in a review process. These tools are organized according to key criteria derived from the initial tool evaluation.

There are four main approaches to Climate Risk Assessment using the CCORAL Tool:

- Screening of climate risks of an initiative;

- End-to-end processes assessment of climate risks of an initiative;

- Find tools in the CCORAL Toolbox for climate risk assessments and management;

- Access to the CCCCC Clearing House documents, books and research on the right side of the CCORAL Tool webpage which enables a progressive study of a topic over a period of time.

4.2. Adaptation Options

Prioritising adaptation options

Climate change projections provide incentives to establish practices that reduce future risks to conditions such as excessive rain. There are many options and opportunities to adapt. These range from technological options such as increased sea defences or flood-proof houses on stilts, to behaviour change at the individual level, such as reducing water use in times of drought. Other strategies include early warning systems for extreme events, better water management, improved risk management, various insurance options and biodiversity conservation.

Climate change projections provide incentives to establish practices that reduce future risks to conditions such as excessive rain. There are many options and opportunities to adapt. These range from technological options such as increased sea defences or flood-proof houses on stilts, to behaviour change at the individual level, such as reducing water use in times of drought. Other strategies include early warning systems for extreme events, better water management, improved risk management, various insurance options and biodiversity conservation.

Note: Water use conservation and demand management programs are an essential component of climate resilience of water resources.

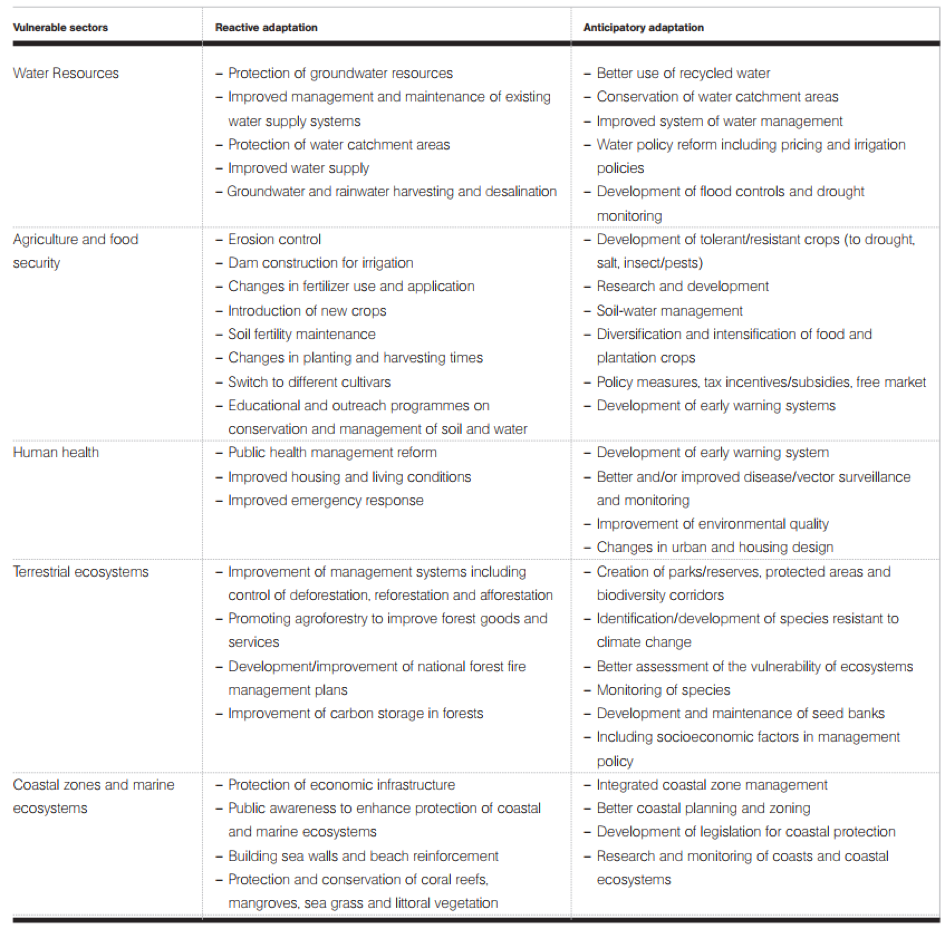

The main sectoral adaptation options and responses highlighted by developing countries in 2007 to the UNFCCC are given in the table below. These include both reactive and anticipatory responses to climate change. Reactive responses are those which are implemented as a response to an already observed climate impact, whereas anticipatory responses are those that aim to reduce exposure to future risks posed by climate change.

Two of the most important operational adaptation options that can be carried out by water utilities are also “no regrets” options. The reduction of NRW and reduction of water demands are operational programs that are vitally important to building a resilient water utility, reducing overall tariffs, and allowing growth while minimizing impact to existing supplies. Therefore, all water utilities should strive to implement these options regardless of projected climatic impacts.

Note: The reduction of NRW and reduction of water demands are vitally important to building a resilient water utility, reducing overall tariffs, and allowing growth while minimizing impact to existing supplies. All water utilities should strive to implement these options regardless of projected climatic impacts.

Adaptation options need to be matched to priorities both in the context of community-based action, in national and sectoral planning as well as disaster risk reduction. Climate adaptation must be integrated into both top-down and bottom-up approaches and across various sectors to ensure sustainable development, a process that can be supported by preparing operational guidelines.

Creating awareness on climate adaptation among planners and political decision makers beyond the environment sectors, and training of stakeholders within these areas, is a useful start. Enhanced funding and capacity building (such as training climate change focal points) are key stages of the adaptation process. National forums could help exchange information on vulnerability assessments, and adaptation planning and implementation at regional level.

Community involvement

Adapting to climate change entails adjustments and changes at every level – from community to national and international (UNFCCC, 2007). Communities must build their resilience, including adopting appropriate technologies while making the most of traditional knowledge. To achieve resilience, the knowledge, experiences and perspectives of women and men, including people with physical disabilities must be taken into consideration.

The UNFCCC (2007) mentions that in Small Island Developing States, adaptation has mostly been taking place through individual, ad-hoc actions on a local scale. For example, in Jamaica, the community has adopted the practice of placing concrete blocks on the top of zinc roofs to prevent the roofs from being blown away during hurricanes since Hurricane Ivan.

These local coping strategies and traditional knowledge should be used in synergy with government and local interventions. Module 3 on Wednesday will introduce the Community Based Water Resilient Assessment Tool. A selection of adaptation measures is given below for illustration. Module 4 on Thursday will focus more on Nature-based adaptation measures for these challenges.

Non-revenue water management

It is not uncommon for some Caribbean water systems to have NRW as high as 50 to 60%, therefore a major focus in reducing water use and thus increasing climate resilience should be directed to reducing NRW. The process of identifying the range and scale of the NRW problem as well as its solution may take several years. Ideally, NRW goals should be set at about 20% in order to maximize investment and increase efficiency (USAID, 2017). It is often less expensive to manage the existing water resources by reducing NRW than to fund new water supply and treatment systems.

The USAID Toolkit (2017) further states: “Typically, water utilities should be able to recover 50 percent or more of the NRW. In most cases, this would be sufficient to meet shortfalls in supply, although the lowest possible figure of resultant NRW should be the goal. Extreme situations where rates of increase in demand are high, coupled with a steep decline in raw water availability due to climate change–related factors, will require a higher rate of reduction in NRW over a shorter (or longer) period as needs dictate.”

Demand management

Efforts to reduce water demand are typically implemented where water demand is high, there is a current supply shortage, or when future demand scenarios show a projected deficit. For instance, several utilities have design parameters that include daily per capita consumption between 180 and 400 liters per person (USAID Toolkit, 2017). In most cases these parameters are rarely met mainly because of a shortage of water coupled with high rates of NRW.

Projected demands for each sector (such as domestic and industrial) and available supply should be calculated, taking into account NRW and a safety factor, to assess the reduction in demand needed. After calculating the needed demand reduction to meet future requirements, the most pressing measures can be identified and implemented. A few examples of demand management measures are water tariffs (higher tariffs for higher use), water audits and water savings fittings (e.g. low flush toilets), rainwater harvesting and reducing industrial consumption (e.g. through on-site reuse).

Marine ecosystems

Several strategies meant to increase marine ecosystem resilience are being implemented in the Caribbean. One such strategy is the establishment of protected areas in coastal and marine areas. Management of these areas may include limiting or prohibiting extractive uses, implementing conservation and restoration of coastal and marine habitats, and designating usage zones to minimize the impacts of recreational use on ecosystems. Another strategy is watershed planning to minimize the transport of land-based pollutants such as sediment, nutrients, and other contaminants to nearshore waters, thus protecting marine habitats from declines in water quality.

Exercise

- Identify the measures, reactive or anticipatory, that are presently being employed within your organization or community.

- Is there more to be done and who should be the implementation agency?

- What level of community training and consultation is needed? Identify 5 concrete ‘next step’ action points to address the shortfalls.

4.3. Case Study: Grenada’s Climate Resilience of the Water Sector Programme

One current project in the Caribbean is the Climate Resilience of the Water Sector in Grenada (G-CREWS) project, funded by the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and implemented by NAWASA, Grenada Development Bank and GIZ, running from 2019 to 2025 (GWP, 2019).

Context

Grenada’s mainland water supply is 90% surface water and is already experiencing the effects of climate change. Supply is further hampered by salinization of coastal aquifers and aging infrastructure. In the extreme drought conditions of 2009-2010, a supply gap of more than 25% occurred. Lack of funds for capital investment and one of the lowest water tariffs in the region hindered the implementation of climate adaptation measures. The lack of a water resources authority and inefficient water use by households and businesses like hotels posed further challenges.

Actions

- Governance: Establishment of a dedicated Water Resource Management Unit outside NAWASA and mainstreaming of climate resilience into water-related sector policies, plans and regulations, such as forestry, land use, agriculture and housing. For example, the inclusion of water efficient equipment for households and business and rainwater harvesting as a new requirement in the building codes.

- Water users: A funding scheme for water-efficient solutions and technologies in tourism and agriculture, such as efficient irrigation systems, rainwater harvesting systems, greywater recycling facilities and water-saving fixtures.

- Water supply system: Increasing storage capacity, infrastructure improvement and introduction of a climate-responsive water tariff (implemented in January 2020), which gives price signals for water users depending on water availability.

Funding

The German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ) was a major contributor to this success supporting Government of Grenada with the by setting up a GCF proposal and acting as one of the executing entities. Islands through the region can only access funds from accredited entities, which are normally development banks or Climate Change Centers etc.

The project is valued at over US$50 million with the total budget financed as follows: GCF: US$42.7 million (grant), Government of Germany: US$2.8 million (grant), Government of Grenada/NAWASA: US$4.6 million (in kind and cash).

Learning

A number of Caribbean SIDS would also benefit from Grenada’s experience and lessons learned with regards to preparing GCF projects. This can be facilitated by exchange platforms on the sub-regional and regional levels, using the Organisation of East Caribbean States (OECS) and CARICOM as hosts for the exchange.

In addition, the project is supporting initiatives in at least 3 other countries to increase learning and replication on GCF project preparation and climate-resilient water sector approaches in the Caribbean. The component is designed to complement the project and stimulate climate action as well as engagement with the GCF in other Caribbean countries.