2.1. Enabling Environment

Institutional environment

Historically, island administrations in the Caribbean have provided water services as a municipal or government responsibility. Such arrangements have complicated the transition to an IWRM approach, as little distinction was made between responsibilities for water services and the management of water resources. This is still the case in most countries, which hinders the effective management of water resources. Next to the clear conflict of interest being both the exploiter as well as manager of a finite resource, often human and financial resources are a challenge and thus water resource management tasks are given lower priority than the water supply services.

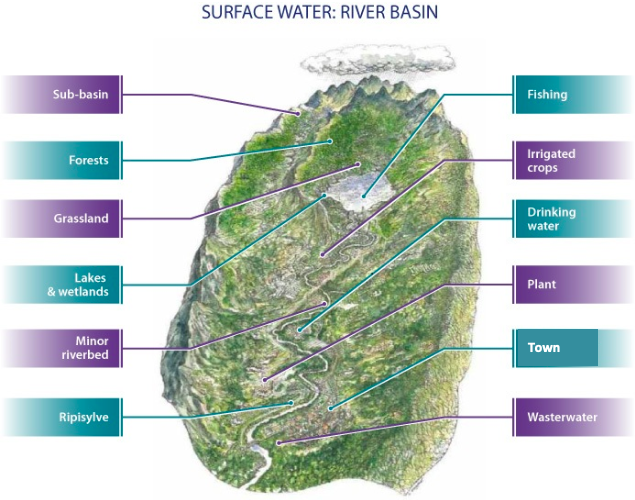

IWRM planning units

A river basin (or drainage basin or catchment) is a hydrological unit related to surface waters. It is an area of land where all rainwater drains into the same river system. It is composed of the main river as well as the tributaries (smaller streams flowing to the main river). The term “watershed” describes a smaller area within the river basin that drains to a smaller stream (tributary), lake or wetland. There are multiple watersheds within a river basin.

Groundwater usually occurs in the form of aquifers, water-bearing units such as sandy zones in the subsurface. The boundaries of the recharge zones of these aquifers usually, but not necessarily always, occur approximately beneath the boundaries of the surface water unit above it. Groundwater and surface water are not separated; groundwater is recharged through the surface water that infiltrates, while groundwater can also be a source of surface water through for example springs.

Understanding the water resources situation and planning their management is usually done at hydrological (river basins) and/or hydrogeological (aquifers) unit levels. However, usually national or state level planning is based on administrative boundaries, and physical and institutional boundaries don’t usually match. Therefore, IWRM planning is carried out at various scales – national level, catchment level and local (sub-catchment) level. The higher-level plans are concerned with more general IWRM objectives, while the lower-level plans include specific interventions.

2.2. Development of a local level IWRM plan

This section shows the process of development of a local level IWRM plan. This level is often the most attainable no matter the policy environment. An assessment by HR Wallingford (2019) showed the greatest impacts in the Caribbean have been through specific ‘demonstration’ projects, usually at the community or watershed level. The message is that IWRM works best when it addresses real issues that resonate with people’s everyday experiences with water and their environment.

The greatest impacts in IWRM in the Caribbean have been through specific ‘demonstration’ projects, usually at the community or watershed level.

In line with the range of roles of utilities throughout the region, the process of management plans has been split up depending on the mandate. Please select below the most appropriate process for you to review.

As policy maker or utility – regulator

Policy makers, water management authorities, as well as (often) water utilities with also a regulator role, are in a position to implement full institutional-based IWRM, concerning wholly integrated activities based on implementation of cross-sectoral activities at a catchment or basin scale. The full process from process initiation to commencement of implementation can take around 2 years for a catchment-level plan. The basic steps of the IWRM planning process are:

- Establishment of a steering committee, formed of women and men

- Establishing multi-stakeholder consultation structures at different levels, such as a basin committee, ensuring representation from each sector, including local communities and the environment

- Preparation of a Catchment Status Report

- Inventory of water resources

- Inventory of water use, including bulk water users

- Preparation of a water balance, for example using a catchment planning model

- Catchment characterisation (policy environment, physical and socio-economic characteristics, gender gap analysis in relation to water management)

- Identifying key issues and challenges within the catchment (based on stakeholder consultations and field work)

- Preparation of the IWRM plan

- Develop catchment vision and key objectives, on socio-economic, environmental and institutional levels (with stakeholder consultations)

- Develop future water demand scenarios (with stakeholder consultations)

- Prioritise results-based interventions and activities, to achieve the goals and objectives, taking into consideration the results of the gender gap analysis (with stakeholder consultations)

- Develop specific interventions (implementation plan) based on the current and future identified challenges, with timelines, output indicators, responsible authority and budget

- Implementation of the IWRM plan

- Monitoring and Evaluation, including lessons learnt (for other catchments)

Example: Jamaica Water Sector Policy – Strategies and Action Plans (Ministry of Water and Housing):

| Water Resources Action Plan | |

|---|---|

| Action/Project | Design and construction of hydrologic databases |

| Planning Horizon | Short term |

| Duration (years) | 1 |

| Cost | US$18,000 |

| Funding source | Grant/GoJ WRA Budget |

| Implementing Agency | Water Resources Authority |

| Remarks | Design has begun in-house |

As utility – non-regulator

As utility without a water authority or regulator role and thus without a cross-sectoral mandate, a ‘light’ IWRM approach can be explored. Light IWRM is the application of the Dublin Principles by individuals and institutions, and within sub-sectors, and at scales below the basin, within the context of their own abilities and opportunities.

Where policy frameworks for river basin planning and allocation are either missing or ineffective, ‘light’ IWRM provides a good start to make the bridges between the sub-sectors. Light approaches aim to develop approaches based on the application of IWRM principles at all stages of the project cycle. The hypothesis is that if all sub-sector actors apply good IWRM practices at their own level, in their own work, this will in turn lead to the emergence of better local level water resource management.

Water utilities can realistically only plan for those water users that are part of their service delivery. These include domestic consumers, and often industrial users as well as agricultural users if these are not utilising private wells. Treated wastewater effluent management can also fall within the scope, if wastewater treatment is part of the mandate of the utility.

The basic steps of a light IWRM planning process are quick, based on local participation and a bottom-up approach. By definition, they are not addressing all aspects (such as socio-economics) and are missing policy aspects.

- Establishment of a working group

- Establishing local stakeholder consultation, with representation of each sector under consideration (such as domestic, industrial, environment), both women and men

- Preparation of a Status Report

- Inventory of water resources

- Inventory of water use

- Preparation of a water balance

- Identifying key issues and challenges, including gender gap issues (based on stakeholder consultations and field work)

- Preparation of the IWRM plan

- Forecast future water demand trends (with stakeholder consultations)

- Develop key objectives to address challenges identified

- Prioritise activities to achieve the objectives

- Develop specific interventions, with time lines, output indicators, responsible authority and budget

- Implementation of the IWRM plan

- Monitoring and Evaluation, including lessons learnt

Example: Jamaica Water Sector Policy – Strategies and Action Plans (Ministry of Water and Housing):

| Area of focus | Improve potable water, sewerage service coverage and operational efficiency |

| Strategy | Encourage conservation and efficient use of water by consumers |

| Activity | Review and upgrade Demand Side Management (DSM) Programme |

| Duration (months) | 6 |

| Cost | US$100,000 |

| Funding Source | MoWH/OUR |

| Implementing Agency | MoWH/OUR |

| Status | Customer conservation programme being implemented – financing being sought for full implementation of DSM programme |

2.3. IWRM Plan Implementation

Monitoring and evaluation

Monitoring and evaluation (M&E) of the IWRM plan implementation is key to ensure insight on which interventions work and why, and what needs to be adjusted. Monitoring helps track progress towards the identified goals and demonstrate the impacts that efforts have. Results from the M&E should be fed back into the planning process.

Exercise for utilities: Water audit (15 min)

One common objective of utility water management plans is reducing water demand on the consumer side. One way to achieve this is a water audit: home-based free audits to identify water-using fixtures and measure their water flow and volume rates. The results of the water audit will provide customers with a specific understanding of where water is used, as well as water-efficiency opportunities, including leak detection. Water audits are great opportunities to motivate and educate customers on efficient water use behaviour. The data gathered during a water audit in customer’s homes can also assist the utility in establishing a baseline for various customer segments and for future strategic and policy planning.

Design a draft water audit process that your utility would be able to implement.

- Which categories of consumers would you target (domestic only, or also industry, agriculture, tourism, etc?)

- How would an audit take place – what are the most important points you as utility want to know, and address (with regards to water wasting behaviour, usage patterns, or leaks)?

- What would the follow-up at consumer-level look like after an audit visit? How could the gathered information be used to achieve the desired water savings, for example providing incentive programmes to install water saving fixtures?

- What would the follow-up process at utility level look like after finalising audits? How could the gathered information be used, for example to optimise internal production processes or improve external communication?

Design a draft water audit process that your utility would be able to implement. Complete the required fields below.